The New US Food Pyramid: Surprisingly Sensible (and What the UK Could Learn)

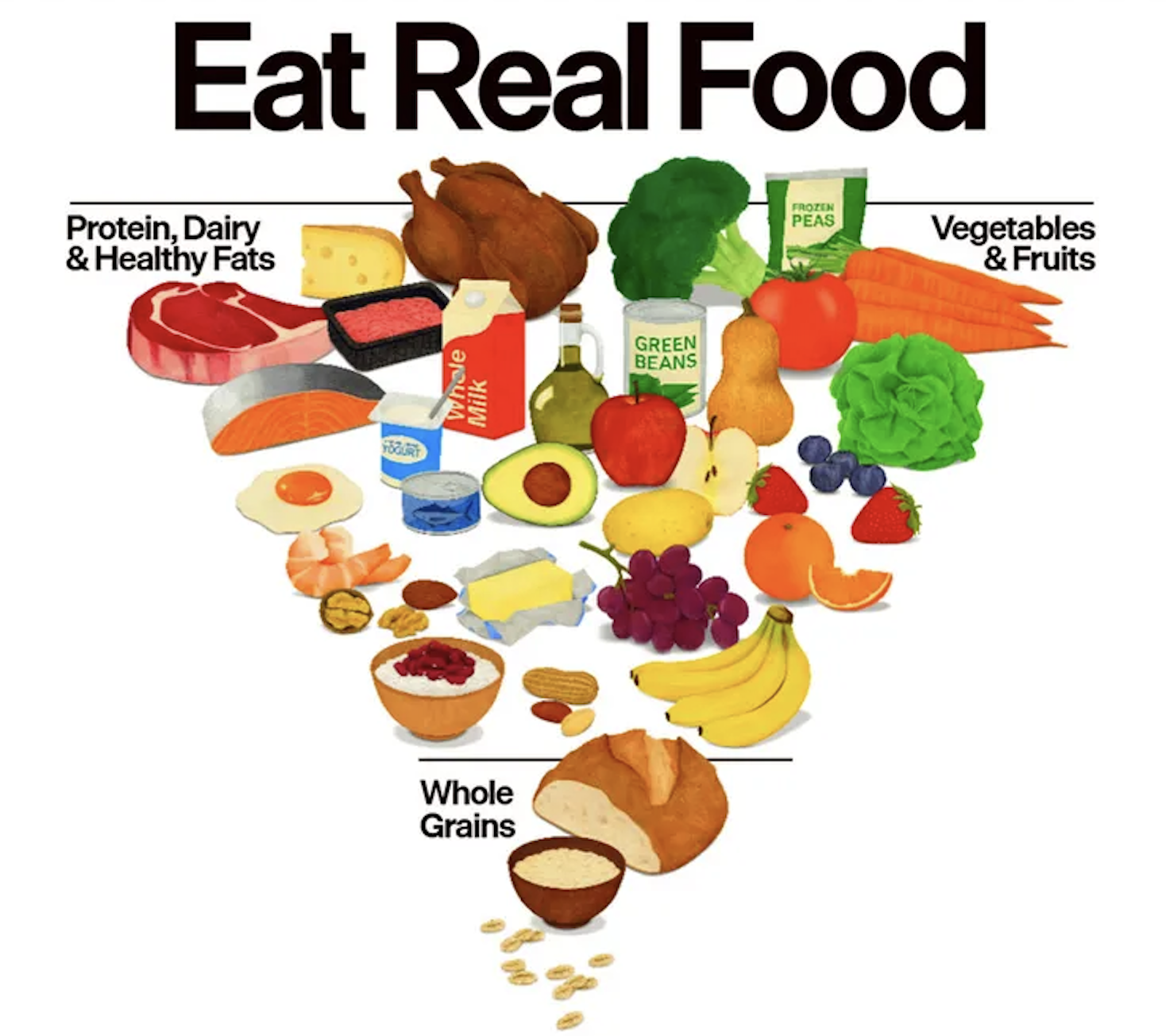

The US “Eat Real Food’ Pyramid has undergone a major update; it flipped the previous one on its head, and I love it!

Refreshingly Boring Message: Eat Real Food

The overarching message is refreshingly boring, which in nutrition is usually a good sign: eat mostly minimally processed, whole foods. This is not controversial, and as a public health guideline, it’s hard to fault.

Prefer to watch than read? Then please check out the video below:

Protein Is Finally Inline With The Research

Where the US has made a genuinely meaningful leap forward is protein. The old recommendation of 0.8 g/kg/day has long been recognised as a minimum to avoid deficiency, not an optimal intake for health, body composition or ageing. The new range of 1.2–1.6 g/kg/day for moderately active adults is far more in line with current evidence. This matters for muscle maintenance, metabolic health, recovery, and functional independence with ageing. In other words, this isn’t “bro science”; it’s basic physiology finally catching up with policy, and I think it’s class!

What’s particularly interesting here, and not something I’ve heard others highlight, is that this change is not cheap. Protein is the most expensive macronutrient to source, store, and distribute at scale. Increasing protein recommendations has real downstream consequences for government-funded food systems: school meals, hospitals, care homes, the military, food aid programmes, and international assistance. Raising protein intake across an entire population is logistically complex and financially uncomfortable. But despite that, they went ahead and did the right thing!

This context likely explains why protein recommendations have remained so low for so long, despite a strong and growing body of evidence supporting higher intakes. Public health guidelines are not written in a vacuum; they are constrained by budgets, supply chains, and political feasibility. From that perspective, the US committing to higher protein targets is a fairly bold move. It’s always easier – and cheaper – to recommend more pasta.

This also helps explain why the UK may be hesitant to raise its own protein RNI (Reference Nutrient Intake) from 0.75 g/kg/day to a similar 1.2–1.6 g/kg/day range. Doing so would force uncomfortable conversations about cost, procurement, and whether existing public food systems are equipped to deliver more protein at scale. Evidence is necessary for policy change, but it is rarely sufficient on its own.

Meat, Dairy, and the Outrage Cycle

There is a bit of online outrage stemming from the visual emphasis on saturated fat, with butter being so high on the pyramid, but context matters. The written guidance still caps saturated fat at under 10% of total energy intake, which is sensible. To suggest actively pursuing a high-saturated fat diet would not be prudent, but complete avoidance would be challenging and ill-advised, as you’d end up avoiding so many very nutritious and high-protein foods, such as steak, eggs, and dairy.

On that note, full-fat dairy has also raised eyebrows, but here again, the evidence is more nuanced than you’d guess from looking at saturated fat in isolation. Full-fat dairy performs well in research, and better than you’d predict based solely on its saturated fat content, likely because foods are not just nutrient spreadsheets – the food matrix matters.

Gut Health and Sugar: Two Quiet Wins

Another welcome update is the explicit emphasis on fermented, probiotic and prebiotic-rich foods to support gut microbiome health. This is no longer fringe science; it’s a rapidly developing field with increasingly robust evidence.

One of the boldest shifts is the language around added sugars. Rather than framing them as something to be “limited”, the guidance now states that no amount of added sugar is needed as part of a healthy diet. Given the lack of nutritional upside and the very clear downsides, this feels long overdue. No one’s health has ever improved because they carefully optimised their Haribo intake. Believe me, I’ve tried!

What the UK Could Do Better

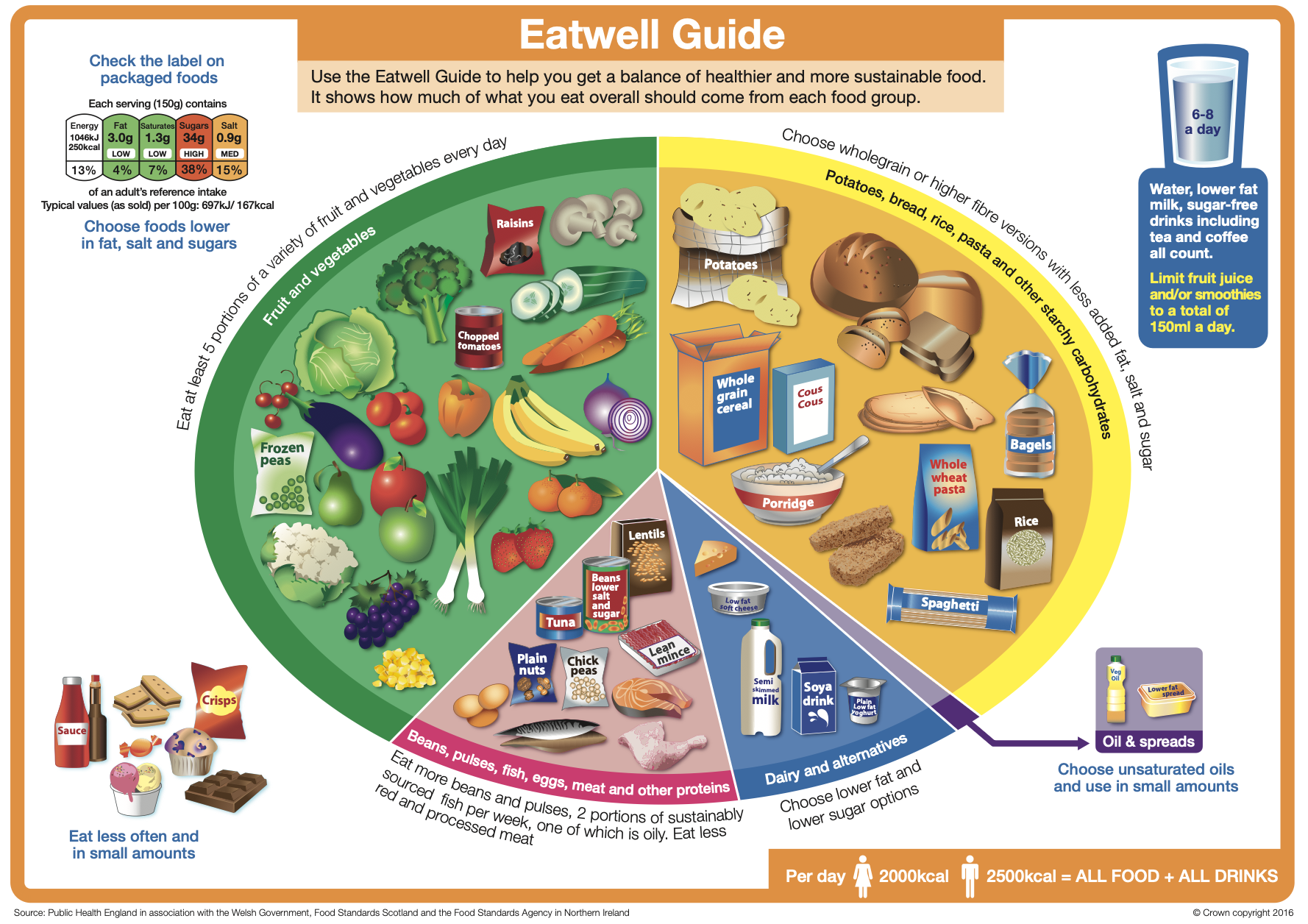

By comparison, the UK’s Eatwell Guide feels dated. It still gives starchy carbohydrates a large portion of the plate, and remains relatively conservative on explicit protein targets. It feels like protein is treated as optional rather than essential.

An improved UK model would look uncomfortably similar to the updated US one: clearer protein targets, greater emphasis on whole and minimally processed foods! They should still probably keep it as a plate, as it visually makes more sense than a pyramid, but a major update is needed.

If the UK starts by increasing protein recommendations, that may cost it a pretty penny, but it will greatly benefit the country as a whole, particularly older adults who need higher protein intake for muscle maintenance and functional independence.

We need to do more to support our ageing population!